At some point in any debate over the legal status of sex work, supporters of prohibitory laws will invariably claim that sex trafficking has skyrocketed in the Netherlands since prostitution was legalised there, that this is a known fact not even disputed by the Dutch authorities and that this proves that legalisation and decriminalisation lead to an increase in sex trafficking.

It’s an argument that has always annoyed me, first because of its obvious cause-and-effect fallacy and second because the Dutch model is not one that is supported by any sex workers’ right advocate that I know of. It’s not unlike invoking the USSR to argue against socialism – in fact, it’s just another logical fallacy, the straw man.

Nonetheless, it’s something that comes up so often I thought it really couldn’t be ignored, so I had a look at the most recent (2010) Report of the Dutch National Rapporteur on Trafficking in Human Beings. The Rapporteur’s role is described on this page:

The Rapporteur’s main task is to report on the nature and extent of human trafficking in the Netherlands, and on the effects of the anti-trafficking policy pursued…

The Dutch Rapporteur works independently and reports to the Dutch government…

The Bureau of the Dutch Rapporteur of Trafficking in Human Beings keeps in contact with and gathers information from individuals, organisations and authorities involved in the prevention and combating of human trafficking and in giving assistance to trafficking victims.

For their information, the Rapporteur and her staff have access to crimnial [sic] files held by police and judicial authorities. Because human trafficking often occurs across borders, the Bureau also has many contacts abroad and co-operates with international organisations.

This, I think, is as close to an “authoritative” source as we’re going to get. The usual caveats about measuring hidden/illegal economies obviously apply.

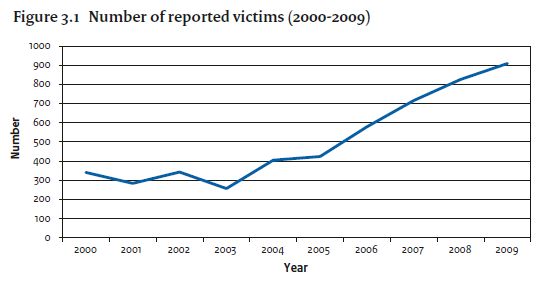

So let’s go straight to the statistics, which are maintained by a body called CoMensha. As sex work opponents claim, these do show a significant increase since the law reform of 2000. Here’s the chart on page 92:

So, case closed? Well, hardly. The Rapporteur herself states that:

The likely explanation for the increase is the intensification of investigations by the police and the public prosecution service, as well as the growing attention to human trafficking. It is also possible that there is greater awareness (and in more agencies) of the need to report victims of human trafficking to CoMensha.

[internal references omitted]

In other words, the numbers aren’t actually increasing, we’re just finding more of them. The Rapporteur could of course be entirely wrong about this; perhaps the recorded increase does reflect a real increase as well. I quote her here only to point out that what sex work opponents portray as an undisputed fact actually isn’t.

But even if you take her words with a grain of salt (she may be independent of the government, but she’s still appointed by them), there are a number of problems with these figures. The first becomes apparent after a moment’s glance at the chart: the number of detected victims actually remained fairly steady for a few years after the law reform, and in fact was significantly lower in 2003 than it was in 2000. Bear in mind, these are only detected victims, and the actual number could have varied in either direction. But on the face of it the numbers don’t seem to support the claim that legalisation itself is behind the increase. You might expect there to be some lag in the law’s effects, but a sharp increase after an initial slump strongly suggests there’s something else going on there.

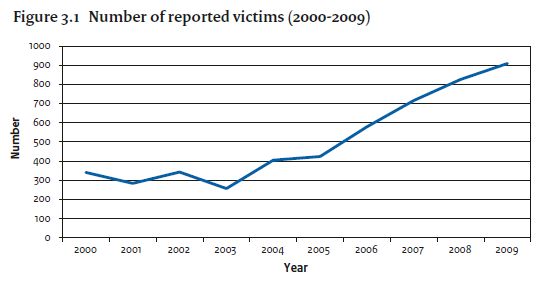

The real spike in the numbers occurred after 2005, and it should be apparent from the shape of the curve that something significant happened at that point. Sure enough: in 2005 the Dutch law on trafficking was amended, to cover non-sexual labour and the trade in organs as well (previously it had only applied to sex trafficking). So, a certain amount of that increase has nothing to do with the sex industry. How much of it? Well, on pages 174-175 the total number of victims specifically linked to the sex sector in the years 2007, 2008 and 2009 is given as 338, 473 and 419 respectively. So here is that chart again, with the number of reported sex trafficking victims for those years noted in red:

In fairness that probably understates the case a bit, since in each of those years there were upwards of 200 reported victims whose sector of exploitation was unknown. I’ll come back to this in a minute, but for the time being we can reasonably assume that some of these were in the sex sector. Even taking that into account, though, it must be clear that the expansion of the trafficking law beyond the sex industry has a lot to do with the impression of a recent trafficking explosion.

Another interesting point is made on page 91. While the usual reaction to statistics like this is to assume that they underrepresent the real numbers – because so many victims go undetected (something I certainly acknowledge) – there is also the possibility that they overstate the case as well. The Rapporteur explains:

it is possible that the persons reported to CoMensha are not all actually victims, so the number of registered victims could also be higher than the actual number of known victims in the Netherlands. This is because there is no formal assessment based on specific criteria by which the registered person’s status as a victim can be verified.

The broad categories of “notifiers” (persons and groups reporting victims to CoMensha) are charted on page 99:

This looks to me as though basically anyone can report a “trafficking victim” to CoMensha, and CoMensha will include that person in its data without ensuring they truly qualify. That must call into question whether the numbers have been inflated through misrepresentation of their actual victim status. A footnote on page 91 says that “very vague reports” will not be registered, but also that CoMensha “has no firm criteria for defining a ‘vague report’”. Also worth pointing out is this bit on page 111:

For almost a third of the victims reported to CoMensha since 2007, it is not known whether they had already been exploited or, if they had been exploited, in which sector.

There are two separate issues here. First, what exactly are the criteria for identifying someone as a trafficking victim if they have not “already been exploited”? I don’t think that identification would be unjustified if, say, they were intercepted en route to a brothel when they thought they were being taken to work in a restaurant, but it’s not at all clear whether that level of certainty is being applied. (I’m reminded of the often-cited statistic of 100,000-300,000 children trafficked in the US every year, which actually refers to children who are simply deemed to be “at risk” of sexual exploitation because of their personal circumstances, such as runaways, and may never actually face exploitation at all.) There’s clearly potential here for erroneous inflation of numbers – and certainly for the statistics to include people who might not be included in the statistics of other countries which only count the “already exploited”.

The second issue is the part about it not being known which sector the victims were exploited in. As mentioned above, these unknowns have accounted for more than 200 trafficking cases per year. What exactly does it mean for a sector to be unknown? That the notifier didn’t know the sector, or that they knew it but didn’t report it? I can certainly accept, given the nature of human trafficking and the trauma its victims can suffer, that it may be possible in some cases to recognise that a person has been trafficked without being able to ascertain the sector. But 200+ per year strikes me as an awfully high number of indeterminate-sector cases, and I would have to question whether some of these reports can really be taken as evidence that trafficking occurred at all. If on the other hand the notifier simply didn’t include the sector in their report to CoMensha, that question doesn’t arise – but you would wonder why CoMensha wouldn’t go back to the notifier and ask for clarification, since it’s a pretty important variable.

Another interesting thing I noticed was in the tables indicating the nationality of victims (pages 160-167). These also include the ranking of the top five nationalities – and the number one nationality of reported victims, since 2004, is Dutch. In fact, Dutch victims have accounted for at least a quarter of all reported victims since 2006, and for nearly two-fifths in 2007-2008. I found that extraordinary. It is true that trafficking can occur within state borders, but it’s fairly unusual for a state to recognise its own nationals as trafficking victims, at least on such a wide scale.

It’s difficult to explain this anomaly without more information, such as a breakdown of the sectors in which the Dutch victims were exploited. The only hint is in the fact that the proportion of these victims who were underage has averaged to 30% since 2006, suggesting that the “loverboy” phenomenon may be implicated. But that doesn’t account for the majority of cases. One possibility could lie in the Dutch definition of trafficking, which to my reading is extraordinarily broad. The UN definition is often said to boil down to “movement, control and exploitation”; however, the Dutch law allows for convictions without any “movement” element at all, within or across state borders. Note Article 1.1.6, which defines a trafficker as anyone who “wilfully profits from the exploitation of another person”. I would suggest that applies to more bosses than it excludes.

If the Dutch authorities are applying this broad a definition of trafficking, is it any wonder the numbers are as high as they are?

In fact, when you take all these qualifications into account it’s quite possible the Dutch figures aren’t excessively high at all (by “excessively high” I mean in comparison with other countries; even one case is too many, of course). Let’s go back to that 2009 figure of 419 sex trafficking victims. Seems a lot higher than Sweden’s 2009 number of 34 (see page 35), doesn’t it?

But first of all, they don’t seem to be comparing like with like. Pages 10-13 of that Swedish report discuss the nationality of the victims and from what I can tell they are all foreign; the report refers specifically to people being trafficked into Sweden. Now this could mean that Dutch people are being trafficked in the Netherlands while Swedish people are not being trafficked in Sweden, but more likely is that Sweden simply uses different terminology for its own nationals who experience “trafficking” within Sweden. So, what we need to compare the Swedish number to is not the total number of reported sex trafficking cases in the Netherlands, but the total number of sex trafficking cases of non-Dutch citizens in the Netherlands. We don’t have that exact number, but the Dutch report states that in 2009, 26% of all trafficking victims were Dutch nationals; if we apply that percentage to the sex trafficking victims we get a rounded figure of 109. Subtract that from 419 and we can estimate now that in 2009, 310 people were reported as sex trafficked into the Netherlands.

Next thing we have to look at is who is doing the reporting. The Dutch figures reflect reports from all sources; the Swedish figures reflect only police reports. In 2009 the Dutch police reported 61% of all Netherlands cases. Applying that figure to the 310, we can estimate that the Dutch police reported 189 cases of sex trafficking into the Netherlands. This is still significantly higher than the 34 cases of sex trafficking into Sweden reported by the Swedish police, but you see how the difference narrows when you take greater care to ensure you’re comparing the same things.

We’re left with figures that suggest a sex trafficking rate in the Netherlands around 5.5 times greater than the rate in Sweden. According to Googled World Bank statistics, the Netherlands’ population is around 1.75 times greater than Sweden’s, making the Dutch rate disproportionate by a factor of 3.75 – you’d expect the Dutch police to report 127.5 cases of sex trafficking rather than 189. So that’s 61.5 cases in 2009 that can’t be accounted for by the population difference alone. I can think of several possible reasons for this extra 61.5 that have nothing to do with the legal status of prostitution (other things that make the Netherlands a more attractive destination country, like its location and climate; or the much broader definition of “trafficker” in Dutch law; or operational differences in Dutch and Swedish police approaches to trafficking), but we really are in the realm of pure speculation at this point.

Of course, we’d need a more detailed set of statistics to really compare the two countries anyway. It’s quite possible that there is actually a wide disparity between sex and non-sex trafficking behind the percentages applying to overall trafficking which I used to arrive at that 189 figure. But that disparity could go either way, so it can’t be assumed that I’m underestimating the real difference between reported cases in Sweden and reported cases in the Netherlands. I could, in fact, be overestimating it and the actual figures could be much closer together. The point of this exercise is not to make any claims about the actual rate of sex trafficking in the Netherlands, but simply to show that there is a wide variety of factors behind the reported rates – and that you can’t simply compare sets of figures from two different countries without considering how all these factors could influence the results.

Another relevant question is how the Dutch numbers after law reform compare to the numbers before it. The most recent Rapporteur report doesn’t give figures from before legalisation, but I was able to find them (in somewhat different format) in the First Report, on page 49:

So clearly the problem was growing in the Netherlands even before legalisation, and perhaps the law change was entirely irrelevant to a trend that was developing anyway. However, even if the law itself had an effect, the report suggests this may be due (at least in part) to a reason that is very different to the one put forward by the anti-sex work movement – and it’s a reason that echoes a point I’ve made over and over again on this blog.

To put it in context: In the latest report, the Rapporteur states (page 26) that the purpose of the 2000 law reform was to

legalise a situation that was already tolerated.

The first report had gone into this in much greater detail, saying on page 11 that prior to 2000

in practice a distinction was made between voluntary and involuntary prostitution and the government in principle limited its concern for prostitution to regulating the exploitation of voluntary prostitution and combating involuntary prostitution. Because the ban on brothels…was still in the Penal Code, this policy in practice meant that the exploitation of voluntary prostitution in the Netherlands was in fact tolerated. This toleration developed in the course of time from a passive tolerance to an active tolerance (Venicz c.s., 2000). Passive tolerance meant permitting the establishment of prostitution businesses, as long as they did not cause any inadmissible nuisance or other articles of the law were not infringed. Active tolerance, on the other hand, meant the government taking controlling action so as to guide developments in a particular direction by various measures. A classic example of this is the system of tolerance orders or licences for brothels and other sex establishments used in many municipalities at the end of the 20th century, by which requirements and stipulations were laid down for their establishment and operation. And so in the 20th century the government did take virtually no action against brothels, except in those cases involving manifest abuses, exploitation of involuntary prostitution or disturbance of public order, peace and safety. In spite of an earlier attempt to amend article 250bis Penal Code in the Eighties, the ban on brothels was finally only abolished from the Penal Code on 1 October 2000.

Now, you might read this thinking that the 2000 law didn’t actually change a thing, and that what we should be talking about here is not what happens when prostitution is legalised but when it is tolerated. But there is an important difference between the two, and it’s one that has been noted in the context of Australian law reform as well:

Police, of course, under a legal system which officially legitimises certain forms of prostitution or certain places, are obliged by the government to enforce laws on other prostitution in order to justify the “legalisation”.

So what are the “other forms of prostitution” which were tolerated in the Netherlands until 2000 and are now enforced against? Well, one of them is prostitution by non-EU migrant workers (or those from EU countries excluded from the Dutch labour market). The legality of sex work notwithstanding, it usually isn’t an option for them unless they have residency on some other ground; it is impossible to get a work permit for the Dutch sex sector and very difficult to get recognition as a self-employed sex worker. And thus, as the sex workers’ rights group De Rode Draad told the Norwegian Ministry of Justice in 2004,

The situation for immigrant women has become much more difficult. Formerly these women’s work was tolerated in the same way as other sex workers’. With the legalisation of one group of women, the work of another group of women now becomes illegal. (page 34)

The Rapporteur’s current report doesn’t really go into this, but it does quote from an earlier report (the third) which addressed it in some detail, noting on page 22 that:

A number of NGOs have repeatedly argued that where aliens cannot work legally in the sex industry in the Netherlands but are still interested in doing so, a ban on or obstacle to doing this legally means a considerable risk of becoming dependent on third parties, with exploitation as a potential and harmful consequence. They therefore regard the ban on issuing work permits for prostitution work in salaried employment and the conditions that are or may be imposed on subjects of Association countries who want to come and work in the Netherlands as self-employed prostitutes as encouraging [trafficking].

So in other words, if it is the case that trafficking has increased as a result of legalisation, it’s because of changes in the government’s approach to migrant sex work, not to sex work generally. It’s an issue of immigration law rather than prostitution law. This, I think, is absolutely critical to a proper understanding of sex trafficking in the Netherlands – whether the actual rate is going up, down or sideways.

What about the claims of exploitation in the legal sector? I’ve seen all sorts of statistics thrown around about this, used to justify the argument that you can’t protect sex workers by legalising the industry. The Rapporteur doesn’t cite any data on this topic, but does accept the existence of these abuses and the failure of Dutch policy to adequately address them. On page 140 she states,

the view that entering the profession was an individual’s free choice that should be respected…may have obscured the sight of forced prostitution, especially since establishing a licensing system for the prostitution sector was expected to make licensed prostitution more manageable, and hence lead to eradication of abuses in the sector. Over the last decade, the emphasis in attitudes towards the prostitution sector seems to have shifted to the vulnerability of the sector to human trafficking. Several notorious cases that have shown that widespread exploitation can also take place in the licensed prostitution sector have undoubtedly been a factor in this.

Well, if Dutch lawmakers assumed that licensing on its own would sort out coercion in the sector then it’s hardly any wonder they’ve had problems. If that was all that was needed, there would be no abuse in any legal and regulated sector, and clearly that is not the case. Here, the report shows the risks not of legal prostitution per se, but of a poorly thought-out scheme which lazily equates “legal” with “non-exploitative”. I suspect that if Dutch lawmakers had taken more input from Dutch sex workers when drawing up their law, this might have been pointed out to them.

Since people frequently seem to have trouble grasping this point, I’ll close by reiterating that these reports cannot be assumed to reflect the actual amount of sex trafficking in the countries they relate to. No really accurate, reliable measure is possible – and the true numbers could be either higher or lower. But if one legal model is going to be advocated over another on the basis of the trafficking rates under those models, those doing the advocating have to find some basis to show that a model has the effect they ascribe to it. This requires showing that, as best as can be determined, not only is there more trafficking under one model than under another but also that there is a causal link between the model and the trafficking rate. The Dutch Rapporteur’s report could support the anti-sex work argument on the first count, but the statistics are not sufficiently disaggregated to say for sure: we don’t know enough about them to pull out all the things that the Swedish authorities aren’t counting and make a like-for-like comparison of the numbers.

The report actually does more to support the claim of a causal link, in the sense that it acknowledges risk factors connected directly or indirectly to legalisation (the laissez-faire approach to the licensed sector and the restrictions on some foreign workers). But the crucial thing here is that these are causal links to the Dutch model of legalisation, not to legal prostitution per se. They could just as easily be used to support arguments for the establishment of a proper inspection scheme, or for allowing non-EU migrants to work in the industry – two things that can only happen in the context of legalisation, decriminalisation or de facto tolerance.

So to answer the question in the title of this post: no, but we shouldn’t discount it entirely either. It may be impossible to say for sure whether the Netherlands actually has more trafficking than other countries, but it definitely has a legal regime which in some ways seems to facilitate it. The reasons it does so may not be the ones put forward by the anti-sex work movement – but that doesn’t make the need for change any less compelling.