Rape is not an ordinary crime. Few people will contemplate whether or not to report being mugged because the police might not believe them. No one sees their car window smashed and thinks “I’m not sure if reporting this is wise. I was drinking last night so the police might think I said it was ok and I consented to them smashing it..”

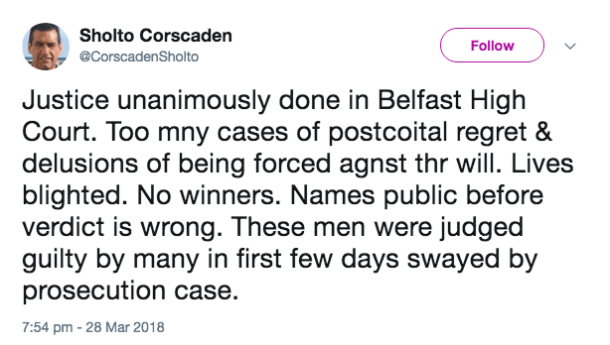

The worst outcome for a rape complainant is that she is not believed. During the Belfast trial, a narrative was created that a the victim had participated in a drunken threesome and then cried rape afterwards because she was worried that “it would be talked about on social media.” The idea that any woman would subject themselves to what is entailed in making a rape complaint, simply because she regretted how she had sex or who it was with, would be laughable if it weren’t so disturbing.

When a woman makes a complaint to police she will usually spend hours or a day (or more than a day) literally recounting her story over and over again; following this she may be brought to a sexual assault treatment unit where trained healthcare professionals will collect forensic evidence and do a head to toe exam collecting samples from under her nails and her hair and her mouth. They will examine her genitals and take photographs. She will likely have to tell her story again to the healthcare practitioners so they know which photos to take. She will not be allowed tea or coffee in case it interferes with evidence in her mouth. Depending on where she lives, she might have to travel for 3-4 hours to get to this unit because her local hospital won’t have one. If there’s a risk of head injuries, she’ll be sent to the Beaumont first, but that has implications for evidence collection of course. If the police believe her, they may send her story to the DPP. They also might not believe her. They also might prosecute her for false reporting. They might laugh at her and snigger it was her own fault.

Rape myths are very common, and police and gardai are as susceptible to them as any other person you meet in the street. Of course, they are not meant to be, but we know they are. They make rape jokes too. It isn’t that long since the gardai were making rape jokes on tape in relation to Shell to Sea protestors. That wasn’t solely about animosity towards protesters, it was because they found rape funny and unless they’ve retired since 2011, they’re still employed by An Garda Siochana. The transcript of that exchange could be a twitter exchange.

^ Garda Rape Tape Exchange

Of course false report convictions are rare much the same way that false reports of rape are rare, but the fear of not being believed and the consequences that follow are a shadow over every victim’s decision on whether or not to report. They are rare, because women do not put themselves through the trauma of reporting because of what it entails, and the glaringly obvious fact that largely, she will not be believed.

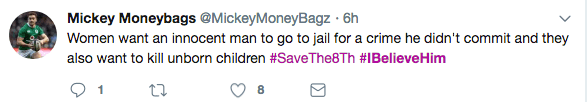

In the best case scenario, if the victim is believed by the Gardaí she must tell her story over and over and over and over again; then if she is believed by the DPP and then after having repeated her story over and over again, a case will be taken. Following this she will listen while her credibility is systematically picked apart by the defence counsel. She will see her knickers passed around the court. Her own credibility will be on trial. They will discuss what she likes and what sex acts she would engage in. The papers will discuss the colour of her labia in print. People on the internet will speculate on where she was in her menstrual cycle and whether the vaginal lacerations she has were from rape or not. Her text messages to friends about being raped will become a matter of public record. A newspaper will write a story in which they wonder whether the blood was from internal bleeding from vaginal injuries or from her period as the defence counsel suggested. In some cases fear of retaliation from the perpetrators will be a worry, whether that retaliation manifests as a physical threat or a threat to make life difficult, or the retaliation might manifest as the forces of privilege in society standing together to paint you as a liar. Anonymous or not, she will be stigmatised and the minutiae of every move she makes will be under scrutiny. Some of the jury will believe that if a woman was drinking, she was asking for it, and other myths, like the style of clothes being an invitation to have grope. Men who barely know the alphabet, let alone the intricacies of criminal law will call for her to be put on trial. They will call for her to be named and shamed. They say this because a lot of society thinks that if you cannot secure a conviction in a rape trial, the victim complainant has been proven to be a liar. Rape trials always mean the victim is on trial as much as the defendants. In the Belfast case, people know who the complainant is, there is no need to name her. Men will share that information. The Belfast verdict in many quarters has been seen as a victory for men. Women will simply return to secret Facebook groups and chats and informal conversations in which the words, “be careful of him” are uttered.

The scale of rape and sexual assault is a global health issue. If one in four people were getting mugged, we would likely examine the root cause and the members of the Oireachtas and other parliaments would probably convene a joint special committee. The media has a key role in this. They, whether they like it or not, shape the public discourse on rape and sexual assault issues. When they produce salacious gossipy reports on the case or the colour of a rape victim’s genitalia in their paper, it matters. It matters because those words are taken and repeated on twitter, with a multitude of shitty opinions attached.

Most rape victims do not report to the police. Convictions do not simply require 12 members of a jury to believe you. They require the police who are questioning your demeanor, level of intoxication and consistency of details, to believe you. Your credibility must be sturdy. Impeccable in fact. It helps if you are not a poor or marginalised woman. During the Belfast trial Stuart Olding’s barrister commented, “Why did she not say no? Why did she open her mouth? Why didn’t she scream? A lot of middle class girls were downstairs, they were not going to tolerate a rape or anything like that. Why didn’t she scream the house down.” The implication being that us working class women would hear it and just go back to adjusting the hun buns and acrylic nails and drinking cans I suppose. The clear message to rape victims in this, and every other trial is “Do not report, it isn’t worth it.”

Reporting to the police means you must be able to withstand victim blaming and questioning and trolling statements and people attempting to hunt your family down on twitter. You must be able to handle that, if you defy traditional gender roles or consume alcohol prior to your attack you are more likely to be attributed a higher rate of blame for your own rape than others. You must be able to overcome whatever obstacles are put in place by privately educated rugby playing people and people who are members of professional associations who have connections and know journalists and other important people.

When you make a report you must be able to deal with the fact that if you were passed out on the ground unconscious and the gardai happen upon you with a strange man kissing your neck and touching you, they may initially think that it isn’t that serious until they find CCTV footage. If you were a teenager working in a low paid carer job providing care for an elderly client, their adult son might sexually assault you. If your rapist was actually convicted, he might initially walk out of the court with a suspended sentence after drugging and raping you in your sleep. If you are 6 years old and your Uncle convinces you to go to your house for biscuits and he subsequently rapes you, he might also get a suspended sentence. If you are a group of five women abused by the same person, he might get a suspended sentence too. Your rapist might even get a partially suspended sentence for sexually assaulting two women having previously finished three jail terms for rape offences. Your uncle who abused you when he was still a priest might get a suspended sentence too. If your rapist dies, the Council might try and pass a motion of condolence for him.

If the text messages from your attackers reference your crying, and imply the group nature of your attack, as if they had great craic during a drinking game, you will still not be believed. This is what society needs us to know.

When your attackers are on trial, it will be you who is made to feel like a criminal. These “talented, promising sportsmen” who all had a different version of events, who deleted text messages and met up when they usually didn’t (but *not* to get their stories straight, remember?) were always going to be found ‘not guilty.’ It didn’t matter that there was a witness testimony confirming the witness’s description. It didn’t matter the taxi driver was concerned and said she was crying. What mattered was that they were privileged men, whose victim was always going to be torn asunder on the stand. Privilege begets privilege. Don’t you always bawl your eyes out and bleed through your jeans in a taxi home after a fun night?

When your attackers are on trial, it will be you who is made to feel like a criminal. These “talented, promising sportsmen” who all had a different version of events, who deleted text messages and met up when they usually didn’t (but *not* to get their stories straight, remember?) were always going to be found ‘not guilty.’ It didn’t matter that there was a witness testimony confirming the witness’s description. It didn’t matter the taxi driver was concerned and said she was crying. What mattered was that they were privileged men, whose victim was always going to be torn asunder on the stand. Privilege begets privilege. Don’t you always bawl your eyes out and bleed through your jeans in a taxi home after a fun night?

The question that many feminists are asking now is why would any woman who witnessed this trial report a rape? If a friend discloses rape, how do you say to her in good conscience “would you consider reporting?”

They don’t want us to. The system is not designed for the victim. It serves an entirely different process. The victim was painted by the barristers involved as a wanton slut who was up for anything. Paddy Jackson, one of the defendants was painted as a poor little boy whose favourite hobbies included “drawing super heroes,” whose only mistake was wanting to have fun.

The complainant in this case did everything that victims are supposed to do, she kept her clothes, she went and made a statement. Experts confirmed vaginal injuries. She told her friends what had happened. The defence still made out that she simply regretted a consensual experience and was afraid she would be labeled a slut. They labeled her a slut anyway not to mention, does any woman in 2018 under the age of 40 really give a fuck about someone having a threesome?

I know an awful lot of victims of rape. So do you. But I have never known anyone that has seen their rapist prosecuted. There are people who are friends of friends but it is truly remarkable that given the scale of it, convictions are rare.

We all know, as women, we are routinely not believed, but for whatever it’s worth, I believe her.

#ibelieveher

As the rest of the post mentions, there’s several outcomes that are arguably worse than not being believed, including being blamed for the offence, blamed for the failure of the prosecution (as per over 90% of reported cases) and blamed for sullying the reputation of the offender. Some complainants go to jail while the offender walks free – even when they are believed.

I’ve spent a fair bit of time and effort over the years proving I don’t know the answer. But I can’t see constructive change coming from the courts, police or media. I reckon a new system to deal with sex offences (and other ‘personal’ crimes that often occur within communities) has to be grown from the ground up from community based centres focused on the needs of survivors, firstly, then other stakeholders; including offenders. I’m thinking along the lines of refuges/shelters/community clinics/resource & referral centres that would include the option of involving the criminal justice system but wouldn’t put it front and centre.

But as well as social infrastructure independent of the punitive arm of the state we need a better response than the adversarial justice system and prison industrial complex.

There’s still a lot of challenges to adapting indigenous models of restorative justice and circle sentencing to modern urban societies, but of all the responses I’ve seen those are the ones that seem most likely to produce something complainants and affected communities might recognise as justice. It’s hard to believe they’d be worse than what we’re doing now.

Pingback: I believe her. – emily rae

She has believed by the police. She wasnt believed by the jury.

I am very happy the justice system isnt based on random internet peoples “beliefs”.

I know many men and women who have been falsely accused of crimes, even if we dont get charged, its socially devastating.

Is it actually true that she wasn’t believed by the jury? I thought the judge instructed a not guilty verdict, that the jury had no choice.

No. The jury made the decision.

Although a person will complain to the police about what they think is a crime, the decision to prosecute is taken by others. In court, it is the state who act as prosecutor, not the original complainant.

In court, the prosecutor has a legal team as do the defendants. The complainant or accuser is not legally represented; it is not the prime duty of the prosecution to represent them. The complainant may have the benefit of ‘witness support’.

Here, the complainant was a witness for 8 days; the defendants in total for 4 days or less.

The defendants are considered innocent until found guilty; the jury must be ‘sure’ or satisfied ‘beyond reasonable doubt’. Thus, the defence will try to sow doubt about the reliability of the complainant, for it often comes down to ‘he said/she said’. That’s not quite the same as not believing the complainant.

The comment you highlighted, about the absence of screaming is interesting; a witness said reportedly that it didn’t seem like a rape to her.

I have only the media reports to go on; these are usually incomplete.

There must be doubt if the adversarial process as used in common law is adequate for rape trials; would an inquisitorial process be more effective?

I wonder; should the complainant in rape cases be legally represented in court? Should such legal representation be allowed to call character witnesses, or to cross-examine the defendants?

Should there be an ‘expert witness’ or ‘assessor’ who can tell the court and the jury what rape is? The judge will instruct the jury about the legal definition, but this is only a very small part of the whole. Here, we know that not all women who are raped scream; they may become passive and hope that it ends quickly. Would an ‘expert assessor’ be helpful to clarify this?

How did the witness who said it didn’t seem like rape know that? Had that person ever witnessed a rape? The media doesn’t indicate if she was cross-examined about this; it might or might not be helpful for the prosecution. In any event, advocates avoid questions to which they don’t know the answer.

Is the legal profession too close to the formalities and processes of an inquisitorial trial to be able to see, as an outsider could, that there need to be major changes if the majesty of the law is to be upheld?

I was raped and I never screamed. I was too scared. I kept my mouth and eyes shut and prayed for it to be over as fast as possible. And I never reported it. It’s taken me years to get as far as even talking about it.

The idea of legal representation for the complainant in a rape trial isn’t new. It is available in Germany. This paper considers the position in Australia, and references Germany:

Click to access 6.pdf

Pingback: Do you know someone who was raped? | Life on an alien planet

Because women are never convicted of maling false rape claims, are they?

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2017/aug/24/woman-jailed-10-years-false-rape-claims-jemma-beale

But you believed her before the trial.

The issue here is not that the whole case was an injustice towards the victim and rape victims but because you had decided the men accused were guilty based on the accusation and before the trial.

I Believe Her is something feminists say as soon as an accusation has been made and before any evidence comes to light for either prosecution or defence.

Its just a way of saying even before a trial “he’s guilty”

All of these people defending the rapists just prove the point. Why would any woman go through such an emotionally draining ordeal only to have it thrown back in your face as soon as everyone finds out that the victim was not some virginal maiden with runny mascara?

Thank you for writing this. We know the stats on false reporting, but even though there is a 98% chance that a woman who alleges rape is telling the truth, there is still this pervasive attitude that most women are making it up or trying to get a man into trouble or ‘consent’ and then regret it later and ‘cry rape’. The reality – that a rape allegation is 50 times more likely to be true than to be false – rarely gets airtime. And if a case makes it all the way to court the possibility that rape did not occur is even slimmer. Because of this, and because of the number of women I know who have not reported their rapes because they don’t want to go through all the trauma only to end up more traumatised and watch their rapist go free, I think it is only reasonable to assume that any man who goes to court as an alleged rapist is in fact a rapist.

I’d be interested in knowing your source for those stats. It’s not something I came across in over a decade of research into sex offence criminology.

Except that we know for sure that men have been tried and convicted of rapes they didn’t commit. It also seems certain there’s men in prison right now for rapes they didn’t commit. I suspect your assumption would seem less than reasonable to them. Quite apart from the implicit abolition of presumption of innocence that would completely undermine our criminal justice system.

You can be fairly confident any abolition of rights of the socially despised will soon be applied to all of us.

Its pretty scary that a growing number of people believe in guilty until proven innocent.

I am going to leave a story from my own life here, because it is relevant:

I left home when I was 13 in fear of my life. I tried going to the police and authorities for help over several months but in those times (1972) we only had battered babies…I was 6ft tall ad did not fit the profile. Understand, my father’s violence was no in any way systematic, it was completely out of control and escalating. I had good reason to fear for my live, just as those who met my funny, charming, balding Tom Hanks lookalike father had good reason to believe he would never hurt a fly…when he went into his third party routine I almost believed him myself – until the third parties were gone.

One day I could not take any more and just started to hitch hike in accord with a plan I had formed over time, not to London, as expected, but to Scotland. I had no intention of ever being found. I had sex with every lorry driver who gave me a ride…I told then I was 22, running from an abusive husband, but if I had sex with them I could relax and stop being afraid of giving the truth away and being handed straight back to the family. I go a lift from a pop group…pretty well known at the time in a “one hit wonder” kind of way. I was drunk, they were stoned off their boxes and it turned into a gang bang. Like Belfast there was one guy who noticed, stopped it all and protected me – unlike Belfast he was the smallest and best looking of them.

I was the victim of so many people that night, and it was only going to get worse.

There is no doubt in my mind I was at least as traumatised as any rape victim, in a way there would never be an opportunity to recover from.

That “one hit” still has the power to feel like the knell of doom and leave me shaking all over even now, almost 50 years on.

But I was not a rape victim…when I was picked up by the Police because I made a mistake and contacted someone a few weeks later I told the truth but refused to name or identify anyone I’d had sex with, including the pop group, because they would have been charged with sex with an underage girl and there was literally no way they could have known I was underage or anywhere near it, and I did not believe they were guilty of any crime.

I still think I did the only right thing (AND I still haven’t had a way to recover from the trauma of any of it – and never will – at the time I was effectively punished for being a victim in every sense).

Now I will leave this story here for anyone who wishes to form their own opinions.

For what it is worth I believe we were doing it all wrong in 1972, and we are still doing it all wrong in 2018, and mob justice is yet another way of doing it all wrong again.