The Irish Department of Justice’s Annual Report of Trafficking in Human Beings in Ireland for 2011 was published recently and I’ve now had a chance to look it over. As you’d probably expect, the coverage of it has been pretty superficial, but that’s not entirely the journalists’ fault: it’s a pretty superficial document, which leaves a lot of really important questions unanswered. That said, no one’s exactly asking them, either.

So here are my thoughts about what this report tells us – and doesn’t tell us – about human trafficking in Ireland in 2011. First, a bit of context. Trafficking is prohibited under the Criminal Law (Human Trafficking) Act 2008, which you can read here. Sections 1-4 are the parts that set out the definition of the offence, and if you don’t mind a bit of legalese it’s interesting to compare them to the international definition set out in the Palermo Protocol on trafficking, which we finally got around to ratifying two years ago. The Irish statute is much wordier, which is entirely typical of domesticised versions of international law: the latter are typically aspirational, unenforceable and constructed through compromise, so detailed definitions are usually neither necessary nor (from a state’s perspective) desirable. The former, however, are the actual law in a country and so need to be drafted with precision.

Length aside, there are three differences I want to focus on between the Irish and international definitions. These are differences in how the two texts deal with what I’ll call the “what”, “why” and “how” of trafficking. The “what” difference is really just technical: in the Irish law (Section 1), “trafficking” itself is a neutral term and is not an offence per se. If you give someone a job, or a place to live, or put them on a bus to another county, you’ve trafficked them. It becomes an offence only if you do these things in a certain way (the “how”) and for a certain purpose (i.e. exploitation, the “why”), which I’ll get to shortly.

By contrast, under Palermo “trafficking” is defined by the simultaneous presence of the “what”, “why” and “how”, so trafficking must always be a crime. I’m not sure that this difference has any practical significance (the Irish statute’s broad definition has no relevancy outside this Act), but it’s one of those things that law nerds like me get excited about.

The second difference, which is much more important, is the restriction that Irish law places on the meaning of “exploitation” (the “why”). Palermo states that

Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs…

The Irish law, on the other hand, spells out what “other forms of sexual exploitation” are included, and draws out (without really adding anything) the non-sexual labour provisions, crucially omitting Palermo’s “at a minimum” phrase. So whereas in international law a highly abusive practice with all the other elements of trafficking could conceivably qualify as such without fitting into any of the specified types of exploitation, in Ireland at least one of the boxes has to be ticked before the exploitation can be deemed to amount to trafficking. This isn’t a criticism of the Irish law; if it did include an “at a minimum” phrase, it could probably never be used or a person convicted under it would have a constitutional challenge for vagueness. But it helps to explain why it can be so difficult to show exploitation amounting to human trafficking, even where exploitation in the everyday sense is obvious.

The final key difference is similar; it’s the way the two texts define the “how”. In the Protocol, it’s

by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person

Here, too, there’s a catch-all that can potentially encompass a very broad range of circumstances. It’s the clause about “abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability”. A person with limited migration and/or employment options is almost by definition in a position of vulnerability; a person with the ability to facilitate or deny them access to those options is by definition in a position of power. What constitutes “abuse” is not defined, and is therefore open to a wide degree of interpretation (and ideological spin).

The Irish law adds a significant qualifier to its version of this clause: under Section 4(1)(c) of the 2008 Act, abuse of this type is only sufficient to bring about a trafficking charge if it

cause[d] the trafficked person to have had no real and acceptable alternative but to submit to being trafficked

So, in Ireland the abuse has to pretty much reach the level of coercion before the law is breached. This is pretty clearly an intentional narrowing of the Protocol’s definition, and gives rise to what could be an important question in adjudicating trafficking cases: who decides what is a “real and acceptable alternative”, and how?

Where children are concerned, both the Protocol and the Irish law have a similar feature in that they both disapply the “how” provisions: as long as the “what” and “why” are present, the child has been trafficked. And the Irish law adds a few things to the “what” of child trafficking. I’ll come back to this later.

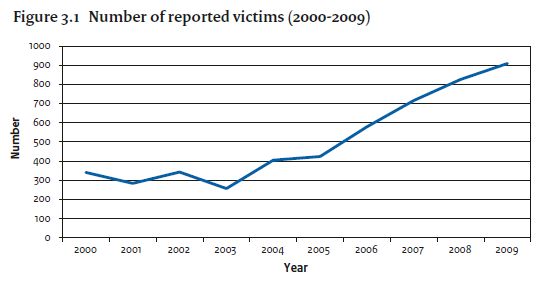

So after that rather lengthy introduction (I didn’t actually think it was going to be that long when I started it, apologies) let’s move on to the actual report. We’ll begin with the statistics since that, unfortunately, is what people are usually most interested in. Page 8 has a table summarising the data on victims reported to the Department by the Irish police, An Garda Síochána:

Then on page 17, there’s a table of the victims reported to the Department by NGOs:

A couple important things here. First, the report states that the figures in the first table should be assumed to largely include the figures in the second table, although the Department’s Anti-Human Trafficking Unit didn’t collect personal data on the victims so couldn’t be entirely sure.

The second important thing is that these are all reported – not confirmed – victims. In the first table, they are persons whom the police investigated as possible trafficking victims. In the second table, they are persons whom the NGOs (according to page 6)

believed exhibited indications of having been trafficked

In a similar vein, that strange “uncategorised exploitation” category in the first chart is explained on page 3 to mean that

while at the time of reporting there were general suspicions that these persons could be victims of human trafficking there were no firm indications that either labour or sex trafficking had occurred

.

So regard must be had to the possibility that in some of these cases there actually was no human trafficking. And the figures, of course, do not take into account those cases that were never detected or reported at all. As with every other human trafficking report in every other country, it is really a record of human trafficking (and alleged human trafficking) reporting, rather than being a record of human trafficking itself.

Page 10 gives a breakdown into age category, cross-referenced with exploitation category. Unfortunately all under-18s are lumped under the heading of “minor”; it would be useful to have more information on where the 7 reported child victims of sexual exploitation and 4 child victims of labour exploitation (plus one each of “both categories” and “uncategorised”) fell on the age scale. It’s all the same legally, of course, but I think there are few people who don’t recognise some kind of difference between a 17-year-old and a 7-year-old – at the very least they would call for rather different preventive approaches.

In terms of the child sexual exploitation, recall what I said above about the broad definition of “trafficking” where children are concerned. Just this week we had this case, in which a man was charged with attempted child trafficking after pulling a girl off her bicycle with the aim of abducting and raping her. A horrific crime, to be sure, but not exactly what most people think of when they see headlines like this. Those who are tempted to see those 13 reported victims as evidence of a growing problem of child trafficking (as it is commonly understood) should bear in mind that some of them may have actually been victims of a type of abuse we’re much more familiar with in Ireland.

Page 11 gives a breakdown of region of origin, and there’s no surprise here: around two-thirds were from outside the EU, which in most cases means they had very restricted, or no, access to the legal labour market. This, as I’ve discussed repeatedly, is a major risk factor for trafficking (both for sexual and non-sexual exploitation). Six of the reported victims were Irish, and the article linked to in the last paragraph says that they were all underage although I can’t find that in the report. Nine were EU citizens, but we don’t know from where – and this is very important, because it too would affect their access to the labour market (Romanians and Bulgarians, remember, are still generally excluded).

Page 14 gives their immigration status:

Under the table is this footnote:

Please note that the reported immigration status reflects the status of persons at the time the information was provided to the AHTU and not when persons were reported to An Garda Síochána.

So with the presumed exception of the EU/Irish citizens, we have absolutely no idea what status the victims entered the country with, or what their status was at the time they were being trafficked within Ireland. That’s a shame, because it would be useful to know whether they’re coming in as asylum seekers, on work permits or bypassing border controls completely (by, for example, crossing the land border with the North). It would also be useful to know how many of them entered the asylum system after being trafficked because the possibility of refugee status offers them their only hope for remaining in Ireland.

On that note I’ll turn to the figure for “Administrative Arrangements”: this is the status for people who have been recognised by the police as victims of trafficking, and allowed to remain for a “reflection and recovery” period. At first glance it seems striking that only one person out of 57 has been granted this status. But there are a couple things worth bearing in mind. First, the main effect of the AA status is to give (limited) protection against deportation – so it doesn’t in any case apply to Irish and EU citizens, who have their own protections already. Thus it’s really one person out of 42. More significant are the figures on page 26, on the “Criminal Justice response to human trafficking”. This states that trafficking investigations are still ongoing in 32 cases (out of a total of 53 – some of these cases account for more than one of the 57 victims); in one case the claim was withdrawn; and in 6 they couldn’t find enough evidence to show that any trafficking took place. In such circumstances, the grounds for recognition really aren’t there. So now we’re down to one person given AA status out of 14 confirmed trafficking cases (that’s assuming that those 14 actually are “confirmed”, which isn’t explicitly stated on page 26 but seems to be the implication). And we don’t know how many of these 14 victims were Irish or EU citizens and so not entitled to AA status anyway. There were 15 reported Irish/EU victims in 2011, so conceivably it could be all of them. On the other hand, it could be none of them. Without better data, we don’t know – but we shouldn’t jump to knee-jerk conclusions based on one quick glance at the overall numbers.

The final thing I want to look at is the breakdown of cases reported by NGOs, by exploitation category and gender. Page 17 states that 22 of the 27 NGO cases were sexual exploitation, and one was labour + sexual. Page 19 says that all of the 27 were female.

It would be easy to cynically assume from this that Irish NGOs just aren’t interested in labour exploitation or in male victims. And, in fact, two of the four reporting NGOs do only deal with sexual exploitation, and one of these only works with women. But the Migrant Rights Centre Ireland, for whom I have huge regard, focuses pretty much exclusively on labour exploitation and takes a gender-neutral approach. And in fact, only a day or two after this report appeared, the MRCI were quoted on the evening news as saying they’d found something like 167 cases of forced labour in the past few years (I can’t find a link to this news broadcast, so you’ll have to take my word for it). So why did they only report 4 cases of labour trafficking last year?

I don’t have a definitive answer to that question, but I can think of a possible explanation. Quite simply, the Migrant Rights Centre exists to promote migrant rights. And human trafficking is not a rights-based concept. It should be, ideally, but trafficking law as conceived at both national and international levels is fundamentally a criminal justice instrument, aimed more at punishing perpetrators than protecting victims.

From this perspective, the Administrative Arrangements would be problematic even if they were liberally applied. Their main purpose (as you can read here) is to facilitate trafficked persons in assisting police with their inquiries. If and only if the person agrees to do so, they will be given temporary residence permission, but it’s clearly envisaged that eventually (i.e., when the investigation is complete) they’ll be repatriated.

That’s great if you’re one of the (very small percentage of) trafficking victims who was forcibly removed from your home country, and you want to return. It’s great if you left home voluntarily but have since decided that you want to return. It’s great if you harbour such (justifiable) ill will toward your traffickers that your paramount concern is to see them punished for their crimes. But if you just want to get on with your life and achieve the goals that you came to Ireland for in the first place? Not so much.

Since the MRCI deals only with victims of labour exploitation, it’s likely that a lot of them would have arrived in Ireland on a work permit. Although a work permit is valid in respect of one employer only, the stated Department of Jobs, Innovation and Enterprise policy is to allow a change of employer in cases of exploitation. (It’s questionable how well this policy is actually adhered to, but at least it’s an option on paper.) Unlike the Administrative Arrangements, a work permit offers a path to long-term residency and citizenship. Why, then, would a person who was subjected to forced labour – at least one who had a work permit to start with – want to pursue it as a trafficking case? There seems to be very little in it for them.

I could be entirely off base here, but even if this isn’t MRCI’s reason for not reporting forced labour cases as trafficking, it’s still a valid concern. The trafficking laws have little or no benefit for trafficking victims who entered the country on work permits – and by the same token, the DJIE policies which do benefit those victims (when they’re actually applied) are not an option for most people trafficked for sexual exploitation. Some researchers lament that victims of forced labour are much less likely to be considered “trafficked”, but it seems in Ireland they might be better off that way.

I said earlier that this is a report about reporting, so perhaps it’s fitting that one of the only things it strongly suggests is that Irish law discourages certain reporting. It’s hard to draw many other conclusions from the report. Trafficking itself is unmeasurable, but the very limited data provision here really doesn’t help us much in understanding what’s going on. Researchers and activists in this field should demand better information, rather than simply seizing on largely meaningless numbers which make easy headlines while actually telling us nothing.